IN

TRIBUTE TO THE LATE RONALD HAVER

The man most responsible for rescuing and preserving the most

complete version of A Star Is Born possible.

|

The

following is his article

"A STAR IS BORN AGAIN"

as published in American Film Magazine's July-August

1983 issue.

Ron

Haver

|

|

This is a preview of his incredible book - A Star

Is Born - The Making of the 1954 Film and its 1983 Restoration

A STAR IS BORN AGAIN

The

search for the missing half hour from George Cukor’s

classic had all the ingredients of a detective story.

Ronald Haver

|

On

July 7 in New York, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts

and Sciences, in association with Warner Bros., is presenting

a most unusual event: the premiere of a restored version

of the 1954 classic A Star Is Born, with Judy

Garland and James Mason. Following the opening, the

new-old film will travel to Chicago, San Francisco,

Los Angeles, and Dallas in a series of single-evening

screenings.

The recovery of this lost classic is a saga in itself,

one marked not only by the passion and diligence of

the researchers, but by the spirit of cooperation among

the various institutions – studios, archives,

trade associations, and agencies, involved in the restoration.

This is a personal account of the effort to restore A Star Is Born to the original three-hour

film that its director loved so much he could never

bear to see the cut version. – Eds.

|

George

Cukor’s 1954 version of A Star Is Born is

legendary for the way it was edited against its director’s

wishes. About a half hour was taken out of the film, and

over the years, among Cukor aficionados, the search for the

missing material took on aspects of the quest for the Holy

Grail.

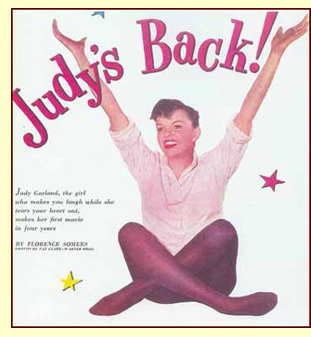

I know, because I’m one of them. I was fifteen when I

first saw A Star Is Born. The ads proclaimed it “the

most eagerly awaited motion picture of our time.” It was

Jack Warner’s all-or-nothing gamble on the comeback of

Judy Garland. She hadn’t made a movie in four years. After

a decade and a half on the MGM roster, she had been fired for

“unreliability,” had a nervous breakdown, attempted

suicide, and divorced her director-husband Vincente Minnelli.

Her third husband, a promoter named Sid Luft, masterminded

her triumphant return to show business.

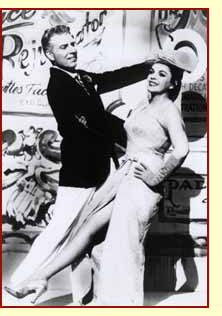

In

early 1953 she and Luft made a deal with Warner Bros.; the

company agreed to finance a remake of David O. Selznick’s A

Star Is Born (1937). Luft would produce, George Cukor

would direct from a new script by Moss Hart, and Harold Arlen

and Ira Gershwin would compose the songs. With James Mason

as the alcoholic movie superstar Norman Main, who transforms

band singer Esther Blodgett (Garland) into star Vicki Lester,

filming got under way; the budget was $2 million. Technical

delays –

caused

by the new CinemaScope process – Garland’s emotional

ups and downs, and Cukor’s perfectionism stretched the

shooting schedule from three months to nearly seven, and the

budget ballooned to an astronomical (for 1954) $5 million.

The picture was given the largest, gaudiest, most spectacular

opening Hollywood had seen in years. On September 29, 1954,

dozens of spotlights formed a huge star over the Pantages Theatre

on Hollywood Boulevard, and more than twenty thousand fans jammed

the area around Hollywood and Vine.For the first time, television

cameras covered a Hollywood opening live from coast to coast.

Life called it “a brilliantly staged, scored,

and photographed film, worth all the effort” and the New

York Times said it was “stunning.”  Several

weeks later, though, Variety carried a short item noting

that Warners would trim A Star Is Born from three hours

to two and a half. Although business had been good, theater

owners had complained that the long running time would keep

the number of showings down to three per day instead of four

or five, thus cutting into revenue. Several

weeks later, though, Variety carried a short item noting

that Warners would trim A Star Is Born from three hours

to two and a half. Although business had been good, theater

owners had complained that the long running time would keep

the number of showings down to three per day instead of four

or five, thus cutting into revenue.

In the film Norman Maine tries to explain to Esther Blodgett

what greatness is: “There are certain pleasures you get

– little jabs of pleasure when a swordfish takes the hook…or

watching a great dancer – you don’t have to know

about ballet. That little bell rings inside – that little

jolt of pleasure. That’s what happened to me just now.”

So it was with me and A Star Is Born one hot Sunday

afternoon. I was disappointed at seeing the shortened version

because I wanted more of those “little jabs of pleasure.”

I wanted more of the art direction – so carefully and

tastefully understated – and of the subtle richness of

the photography that filled the huge CinemaScope screen with

compositions I’d never seen in a film. I wanted to see

and hear the two missing musical numbers. I wanted more of the

Moss Hard and Cukor’s observations of the Hollywood social

scene, the studio atmosphere, and the ambience of Los Angeles

and its environs, more of the elegance and wry sense of humor

that permeated the film. But Warners had withdrawn the three-hour

version, and it never reappeared.

In 1971, when I was a projectionist in Los Angeles at The American

Film Institute, I had the chance to see all of George Cukor’s

films. Cukor and Gavin Lambert were screening them during research

on Lambert’s book On Cukor. I was completely in awe of

Cukor, who was as witty, as elegant, and as forthright as his

work. I asked him if we could screen his personal print of A

Star Is Born. “I don’t have a copy,”

he said. “I don’t have any of my films. All I have

are scripts and stills.” I implored the AFI’s film

librarian to try to get the 181-minute version from Warners.

Back came the word: All the studio had was a stereo print that

ran 154 minutes. The day of the screening, Lambert showed up

alone. “Where’s Mr. Cukor?” I asked. “He’s

not coming,” he said. How strange, I thought, not to want

to see one of your best films. His reason was later given in

a remark recorded in Lambert’s book” “Judy

Garland and I felt like the English queen who had ‘Calais’

engraved on her heart…neither of us could ever bear to

see that final version.”

Two

years later, when I was working at the Los Angeles County Museum

of Art, with archivist David Shepard, we decided to show A

Star Is Born as part of a Cukor retrospective, and to accompany

it with a brochure, using stills and script extracts, to show

exactly what had been cut. Cukor lent us his script and his

complete collection of still from the film, and we were able

to finally itemize just exactly what had been taken out, and

assess the damage to the story.

In

the picture as it has been seen for the past twenty-nine years,

Norman Maine, after hearing Esther Blodgett sing in an after-hours

dive, talks her into quitting the band she’s been working

with and promises to get her a screen test.  She decides to take

him up on the offer. Fade out. Fade in: She’s at the studio

being made up for her test. She decides to take

him up on the offer. Fade out. Fade in: She’s at the studio

being made up for her test.

Originally, there were nine additional scenes between the offer

and the screen test. Esther the next morning says goodbye to

the members of the band, while across town a hung over Norman

is being poured into a limousine and taken off to a midsea location

for three weeks. She waits for his call; meanwhile, he, out

at sea, is making frantic efforts to locate her, but cannot

remember the name of the motel where she is staying. In the

ensuring weeks, Esther tries for find work, moves to a cheap

rooming house in the downtown Bunker Hill section of Los Angeles,

gets a singing job (doing voice-over for a puppet commercial

for shampoo), and finally ends up as a carhop at a Sunset Boulevard

drive-in. Norman, having returned, hears her voice on the television

commercial and tracks her down. They have an awkward reunion

on the roof of the rooming house, which then fades to the studio

makeup scene.

Also removed from the film was a two-minute scene of Norman

driving a nervous Esther, now Vicki, to the preview of her

first starring picture, trying to calm her; she makes him stop

the car and gets sick all over an oil derrick. Another deletion

was a five-minute segment showing Vicki recording a song while

Norman watches; afterward, his marriage proposal and her refusal

is picked up by an open microphone and played back by the engineers,

leaving her no choice but to accept. The final deletion removed

both of Vicki’s renditions of the song “Lose That

Long Face’; one had followed Norman’s drunken humiliation

of her at the Academy Awards ceremony, and the other had come

immediately after her dramatic breakdown in her dressing room

with Oliver Niles, the producer (Charles Bickford). A total

of twenty-seven minutes was taken out. The deletion of the growing

emotional involvement of Norman and Esther eliminated much of

the story’s poignance and diminished its tragedy.

I was very proud of the brochure; George looked at it cursorily,

murmuring, almost to himself, “They don’t deserve

a good picture,” and then beyond a brief “It’s

very nice” never said another word. Evidently, it only

served to remind him of one of the major disappointments of

his career.

One

thing the brochure did was to generate renewed interest at

Warner Bros. In finding the missing footage. Rudi Fehr, then

vice-president in charge of post production, told me that he

had his people to through their records and storage vaults

and that they turned up nothing.  Evidently, the cut sect6ions

had been kept for several months and then destroyed, a common

practice at most major studios. I was convinced that if I could

get free, unlimited access to the studio vaults, a careful

combing through all those thousands of cans of film would turn

up the footage, possibly in mismarked cans. But studios don’t like novices, no matter how well

meaning, rummaging through their vaults, so it looked as though

I wouldn’t get the chance. Evidently, the cut sect6ions

had been kept for several months and then destroyed, a common

practice at most major studios. I was convinced that if I could

get free, unlimited access to the studio vaults, a careful

combing through all those thousands of cans of film would turn

up the footage, possibly in mismarked cans. But studios don’t like novices, no matter how well

meaning, rummaging through their vaults, so it looked as though

I wouldn’t get the chance.

One day, from out of nowhere, came a call from an apprentice

film editor at Warner Bros. Named Dave Strohmaier; he told me

that he had come across the complete mixed soundtrack to the

three-hour picture. He had not, however, been able to turn up

any footage. Then, one evening in November 1981, at the Academy

of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, I hosted a tribute to lyricist

Ira Gershwin, which ended with an excerpt from A Star Is

Born: Judy Garland singing “The Man That Got Away.”

Introducing the finale, I commented on the fact that two of

Arlen and Gershwin’s best songs had been removed from

the film. Fay Kanin, president of the Academy and someone with

a long and close relationship with George Cukor, said afterward

how wonderful it would be if the complete version of the film

could be found.

In addition to being a writer of great sensitivity (Friendly

Fire, Hustling), Fay, who has a deep-seated and

passionate commitment to film, to film history, and to preservation,

is a member of the AFI Board of Trustees’ Preservation

Committee, chaired by Jeanine Basinger and including Brian O’Doherty

of the National Endowment for the Arts, Jean Firstenberg of

the AFI, Mary Lea Bandy of the Museum of Modern Art, and several

other individuals concerned with national archive issues. At

the request of the committee, the AFI’s board has designated

the next ten years the Decade of Preservation. A Star Is

Born seemed a perfect vehicle to highlingh the problems

of preservation. Questions had already been raised about the

stability of the film’s color negative; the mater stereo

sound tracks had evidently been erased years ago; and existing

prints were on the old Eastmancolor release stock, which has

a tendency to fade. So Fay contacted Robert Daly, chairman of

the board of Warner Bros., and he eventually granted permission

to go through the company’s film-storage facilities.

In

late spring 1982, I began my search on the East Coast at the old,

meticulously maintained Vitagraph storage facilities in Brooklyn,

owned by Warners since the late twenties. Nothing useful there,

though, and the same was true of the laboratories in midtown Manhattan

that had struck the prints. The next stop, back in Los Angeles,

was the Technicolor labs in Universal City, where I was aided

by Bob Schulte, who went through the history of A Star Is

Born’s print holding with me. Technicolor had made

the first set of prints for the full-length road-show version

in 1954; according to its September 1954 records, the company

struck 150 four-track stereo prints on Eastmancolor stock for

the first run. No more additional work was done until an order

came through to cut the master negative.

When A Star Is Born was cut, reels 3A and 3B were combined

to form a new, shorter reel known as 3AB. Cuts were also made

in 4A, 5A, 6B, 9A, and 9B. The excised negative material, the

“Trims and Deletions,” as the order phrased it, were

put in ten cans and shipped to the studio.

A later print order called for another 150 prints of the short

version made by the Technicolor dye-transfer process, to be used

during the second run. From the shortened master negative were

also made all the subsequent printing materials for 16mm and foreign

35mm use. So much for finding a full-length 16mm or overseas print.

The next step was trying to determine what happened to the 150

full-length four-track prints. According to the old studio files

now kept at the University of Southern California and the Warner

Bros. Distribution records at Princeton University, orders went

out in 1954 from the editorial department to all the film exchanges

across the country, telling them how to cut the prints and instructing

them to send the excised material back to the studio. We thought

perhaps some zealous editor-inspector might have kept the extra

footage.

During

the summer months, the Academy placed ads in trade publications,

but turned up nothing of interest.

Everything seemed to point to the studio.  If the material wasn’t

there, then it was pretty certain not to exist. Warners’

editorial and film library is under the calm but firm control

of Fred Talmage, vice-president in charge of postproduction, the

nerve center for everything that happens to a picture after it

comes off the sound stages. When I told him that I wanted to spend

my summer vacation prowling through the studio vaults, Fred just

smiled, shook his head, and said, “Well, Ron, Whatever

turns you on.” If the material wasn’t

there, then it was pretty certain not to exist. Warners’

editorial and film library is under the calm but firm control

of Fred Talmage, vice-president in charge of postproduction, the

nerve center for everything that happens to a picture after it

comes off the sound stages. When I told him that I wanted to spend

my summer vacation prowling through the studio vaults, Fred just

smiled, shook his head, and said, “Well, Ron, Whatever

turns you on.”

Our first stop was the Sound Department’s storage area under

what is known as the old Technicolor building to make certain

that Dave Strohmaier had been correct about the complete track

being there. It’s a huge subterranean basement, stretching

under the studio for nearly a quarter of an acre, lit by bare

bulbs, and in some areas thick with a fine dust that covers thousands

of cans of sound tracks and magnetic tape. Two Sound Department

veterans, Ed Chaplin and Phil Birch, took Fred and me through

the narrow aisles. We began pulling out cans marked “A STAR

IS BORN, Long Version YD-YF Mag Track,” which meant that

this was a monaural dialogue, music, and sound effects track on

magnetic film. There were twenty-three cans, and the only way

to find out if they were what we were looking for was to play

back one of the reels to see if it had the missing material on

it. Reel 3A was pulled; if all was well, it would have Esther

saying good-bye to the band – and by God it did! Things

were off to an auspicious start.

Finding the sound track was half the battle; now all we had to

do was locate the picture to match it. Fred turned me over to

Don Adler, who’d been working in the film vaults for almost

thirty years, cataloging every single piece of exposed film on

its journey from camera to release print. I asked him what would

have happened to the cans shipped back to the studio from Technicolor

containing the cut negative. “In those days,” he said,

“we’d keep it for six months, then junk it.”

Was it possible that some of it might not have been junked? “Possible,

but not likely.” According to Don’s inventory, there

were some miscellaneous cans of A Star Is Born material

in one of his storage areas. There were about twenty cans, none

of which had the appropriate Technicolor numbers on them.  Not

one of the reel numbers on the cans corresponded to the reels

that had been trimmed, but here was my chance to prove or disprove

my theory about the possibility of mismarked cans. Not

one of the reel numbers on the cans corresponded to the reels

that had been trimmed, but here was my chance to prove or disprove

my theory about the possibility of mismarked cans.

I

wound through the film, squinting at the 35mm images, looking

for something that was familiar to me from the stills of the

missing sequences. Can 7A had the first love scene between Norman

and Vicki, immediately after her preview triumph. It takes place

on the terrace of an exclusive Hollywood nightclub and is supposed

to dissolve into a scene in producer Oliver Nile’s office,

when they announce they’re going to be married. Instead,

I found I was staring at the missing scene on the recording stage

with Vicki singing “Here’s What I’m Here Fore,”

followed by the proposal and live microphone pickup.

I must have let out a loud yelp, because Don came running back

into the office to see if something had happened to me. I was

jumping up and down with excitement. If this one sequence was

there, could the others be far off? Don helped me carry in the

other cans of film, and I reeled through negative can after negative

can, hoping that lightning would strike twice. It didn’t,

but for the next two days I examined every single rack and every

single label on every single can of film in that basement storage

are.

“Where next?” I asked Don. “Try the stock-footage

library,” he replied. “I think they have a lot of

leftover material from the film.” Every studio has one of

these libraries;’ after a picture is put together, an editor

goes through all of the unused film and selects material that

might be useful in some future film. The Warners stock-footage

library is under the iron rule of Evelyn Lane, an imposing woman

who stands for no nonsense from anyone. Her long days are spent

in a cramped bungalow office stacked with miscellaneous cans

of film, overflowing file cabinets, rewinds, and editing tables.

“A

Star Is Born? Down there in the bottom drawer,” she

said, pointing while cradling a telephone on her shoulder and

typing up a requisition slip. She hung up and swung around t

explain that all fo the Warners features are listed by title,

with individual index cards for each piece of stock footage from

the movie.  She pulled out the bottom drawer and there, neatly

typed on five-by-seven-inch cards, were the descriptions of all

the unused negative segments from A Star Is Born, with

a sample frame of each negative on each card. They were all broken

down into subject categories - “Apartment Houses,” “Automobile Traffic,”

Drive-in,” “Life Rafts,” “Los Angeles

Exteriors’ – with a one-line description of what was

one each piece of film. I pulled out the card marked “Bus”

and read, “Day. But with lettering GLENN WILLIAMS ORCHESTRA

on side pulls away from Motel.” I began to get excited again.

This was Esther’s good-bye to the band. She pulled out the bottom drawer and there, neatly

typed on five-by-seven-inch cards, were the descriptions of all

the unused negative segments from A Star Is Born, with

a sample frame of each negative on each card. They were all broken

down into subject categories - “Apartment Houses,” “Automobile Traffic,”

Drive-in,” “Life Rafts,” “Los Angeles

Exteriors’ – with a one-line description of what was

one each piece of film. I pulled out the card marked “Bus”

and read, “Day. But with lettering GLENN WILLIAMS ORCHESTRA

on side pulls away from Motel.” I began to get excited again.

This was Esther’s good-bye to the band.

There were nearly two hundred entries for A Star Is Born,

and some of this negative material had been printed up for possible

use. Evelyn took me to the vault holding the printed material,

and I began going through dozens of cans, finding numerous takes

of the film’s scenes, mostly long and medium shots, carefully

edited to that the principals are not visible.

Hoping there might be more than this among the negative material,

I asked Evelyn to take me to that storage vault, made up of long,

narrow concrete bunkers filled with rank upon rank of film cans

– 150 of them from A Star Is Born. Each can had

several tightly wound rolls of negative material with a paper

label describing the contents. The label on can number 90 read:

“Judy Garland sings ‘Lose That Long Face.’”

The anonymous stock-footage editor had saved every alternate

take of the musical numbers in the film, including the puppet

commercial. There seemed a good chance that all the missing dramatic

footage, in alternate takes, might be here too.

For the next three weeks I went through the 150 cans, examining

every roll, but the all-important close-ups and medium shots of

the leads playing the deleted scenes were nowhere to be found.

My last hope was the storage vaults for the library prints, the

copies that are kept for use by the studio. I worked my way through

all these vaults, finding nothing, until finally only one more

remained.

Vault 120 looked no different from all the others before it, except

that in the back were some tall cardboard boxes of the type that

film cans are shipped in. Near the airduct grating in the very

rear were two boxes, about three feet high, sealed with no labels

other than the Technicolor emblem. I opened the first one and

looked at the cans: The Bounty Hunter, a Randolph Scott

Western from 1954. The other box was sealed tightly with masking

tape. From the look of it, it had never been opened, but I finally

managed to peel off the tape and break open the sealed top. There

was a silver can inside with the distinctive blue Technicolor

label, and on the label were the words “A STAR IS BORN R12A.”

a yellow shipping receipt had the date, October 4, 1954.

I opened the top can, and inside were the black waxed bags that

film is shipped in; they had never been opened. I began pulling

out those cans furiously, looking for two separate reels, 3A

and 3B, which would tell me that this was a complete, uncut print.  By the time I got down to the bottom of the box, I was shaking

so much that I dropped my flashlight and had a hard time reading

the numbers on the top; there was 4B, then 4A, and finally “Reel

3AB.” By the time I got down to the bottom of the box, I was shaking

so much that I dropped my flashlight and had a hard time reading

the numbers on the top; there was 4B, then 4A, and finally “Reel

3AB.”

It was the cut version. I sat there for a couple of minutes,

completely dejected; there was nothing to do but admit that everyone

had been correct – the missing sequences were irretrievably

lost. However, about 20 minutes of usable deleted footage, a

complete, 181-minute monaural soundtrack, 154 minutes of stereo

sound track (which was on the studio print), and the mint-condition

Technicolor short version had been found.

I

occurred to me that we could take the bits and pieces of film

that we ’d found in the stock-footage vaults, and, using

the sound track and the editor’s script as a guide, put

the shots back where they belonged. The several minutes where

we had no visuals could be filled in using stills of the missing

scenes. Stills have been used successfully before, notably in

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Raging Bull, but never

before in a restored film. Robert Swarthe, special effects genius

and animator par excellence, told me it could be done, but it

would be expensive – maybe $25,000. Lisze Bechtold Blyth,

a prizewinning animator, agreed to take on the project, if we

could get approval and money.

Once Fay Kanin got the approval of George Cukor and Gene Allen,

production designer on A Star Is Born, she went back

to Robert Daly and asked for Warners’ financial support

in reconstructing the film and help in setting up a series of

fund-raising screenings for the Academy’s ongoing archival

work. Daly was interested, but cautious. He proposed that we do

a test reel, and authorized $5,000; we said we’d come back

in tow months. The day after the meeting, Lisze, Gene, the Academy’s

Douglas Edwards, a young editor named Craig Holt, and I began

meeting in the Academy’s editing room. We decided to start

right at the beginning of the deletions, with Esther’s farewell

to the band, and then go through Norman’s being drive off

to location. Esther’s waiting for his call, and all of the

other missing bits right up to Esther’s doing the voice-over

for the puppet commercial. Evelyn Lane pulled the negative segments

we needed.

We were nervous about the color quality, but the material, when

it came back from the laboratory, looked absolutely beautiful.

Craig and I began the arduous task of looking at the various takes

and trying to match them with what was happening on the sound

track. It was much like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. We cut

in blank film w3here we had no picture; then Lisze, Gene, and

I timed this blank footage, and worked out the camera moves across

the stills.

All this took almost five weeks to work out, and on the day that

Lisze brought in the results of her first shooting, we were all

a bit nervous. The lights went down, the picture faded in, and

the camera traveled across a still of the Glenn Williams Band

bus, coming to rest on Judy Garland as, on the track, voices of

the men in the band said their farewells. It looked wonderful,

and the sound and the image matched up beautifully.

So Fay set up a screening for Daly; George Cukor was going to

attend, too. But the night before the screening, the telephone

rang and I was told that George had died. I was stunned.

It

was a very depressed group that met at the Academy’s Samuel

Goldwyn Theater on the evening of January 25, 1983. However,

Fay reminded us that we had a great opportunity here. In reconstituting

the film and presenting it to audiences, we would not only be

restoring a marvelous movie but celebrating George. Suddenly

there was a renewed spirit of commitment, shared by Daly when

he arrived. The picture looked and sounded spectacular, and three

days later Fay excitedly called to say that he had agreed to

back the project. It

was a very depressed group that met at the Academy’s Samuel

Goldwyn Theater on the evening of January 25, 1983. However,

Fay reminded us that we had a great opportunity here. In reconstituting

the film and presenting it to audiences, we would not only be

restoring a marvelous movie but celebrating George. Suddenly

there was a renewed spirit of commitment, shared by Daly when

he arrived. The picture looked and sounded spectacular, and three

days later Fay excitedly called to say that he had agreed to

back the project.

Then came another lucky break. At the Academy’s urging,

Jim Parker of Eastman Kodak agreed to donate the raw stock that

we needed to complete the project. The longevity of the color

negative had been verified by the beautiful prints we were getting

from the stock footage. We wanted to print our restored sequences

on the new Eastman Kodak print film 5384, with its vastly improved

dye stability. This gift freed a large chunk of our budge, which

could then be used to restore the stereo sound track.

Craig, Lisze, and Gene worked days, nights, and weekends, joined

by D.J. Zeigler of the Academy’s Film Department and Fred

Talmage and his technical staff at the studio, to finish in time

for the public showings. A Premiere was set for July 7 at the

Radio City Music Hall, with screenings to follow in Chicago,

San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Dallas.

These presentations will serve to advance the cause of film preservation

and to remind audiences of the achievements of George Cukor, Judy

Garland, James Mason, Moss Hart, Harold Arlen and Ira Gershwin,

musical director Ray Heindorf, cinematographer Sam Levitt, and

the dozens of other Hollywood crafts people whose work made A

Star Is Born the overwhelming theatrical experience that

it will once again prove to be. Finally, the presentations will

serve to give audiences the chance to experience hundreds of “those

little jabs of pleasure.”

Ronald Haver

American Film Magazine

Volume VIII Number 9

July-August 1983

top of page |